HOMEWORK | WEEK 3 | Review

- If you have any outstanding validation errors in your bio and resume HTML, resolve them. Also, if you receive any comments from me today in class, or via email in the following week, incorporate them into your pages.

- Using all the properties we have covered today, create a single, external stylesheet and apply it to both your bio and your resume pages.

- Post the new work and link it to your homework page.

- Go back into your index.html, artist.html, resume.html and contact.html pages and add div’s.

- Create a style.css page in Text Wrangler and link it to your index.html, artist.html, resume.html and contact.html pages. Add the div names in your css page and STYLE them including font, color, size and any other attributes you want to use.

- Take any 12 images. They can be photos, illustrations, your artwork, anything you have. If you do not have anything you can pull images from Google images or create different colored boxes and use those as images. Create two different sizes of these images, one thumbnail image and one full size image. The full size image should not exceed 800×600 pixels. Use the “Save for Web” process to optimize the images, saving them in the file format most appropriate for each image. Save these images to the “images” folder you created in week two.

- Create HTML / CSS using the thumbnail size of the images that duplicates the functionality of the thumbnail gallery that we went over in class today. Take the thumbnail gallery one step further – link each thumbnail to its full sized image. Post the files and images to your server and put the link to the gallery on your blog.

- Embed a video on one of your pages.

- Add a background image.

- Make one of your images link to another website.

- Add at least one image that has rounded corners.

- Add ALT, HEIGHT & WIDTH properties to all your images.

- Add a border to one of your pages.

- Complete 1-5 on CSS in Code Academy

IMAGE REPLACEMENT ROLLOVER FOR YOUR MAIN NAV

You can see a great example of image rollover on the Apple website.

Take a look at the image replacement rollover.

<ul id="navlinks"> <li id="home"><a href="#">Home</a></li> <li id="navprojects"><a href="#">Projects</a></li> <li id="navclients"><a href="#">Clients</a></li> <li id="navevents"><a href="#">Events</a></li> <li id="navabout"><a href="#">About</a></li> <li id="navcontact"><a href="#">Contact</a></li> </ul>

</div>

- Image replacement CSS The key to this technique is to use a single image, containing all the navigation menu items and all of their states.

Then, set up a unordered list of links in your html page. This is a nice semantic way to represent navigation:

Make sure that you give the ul and each li unique ids.

Then, in your CSS, you can use link states (a, a:hover, a:active, a:visited) and background position to reveal the appropriate section of the background image.

An explanation of what the box model is and how it is treated by different user agents.

The term “box model” is often used by people when talking about CSS-based layouts and design. Any HTML element can be considered a box, and so the box model applies to all HTML elements.

The box model is the specification that defines how a box and its attributes relate to each other. In its simplest form, the box model tells browsers that a box defined as having width 100 pixels and height 50 pixels should be drawn 100 pixels wide and 50 pixels tall.

There is more you can add to a box, though, like padding, margins, borders, etc. This image should help explain what I’m about to run through:

Let’s go to this website to check out the full tutorial on box models.

RULES AND SELECTORS

To style elements in a document, you apply rules to selectors. A “selector” is a way of referring to some specific element or group of elements on a page. If you want to apply a style to all paragraphs, then the <p> (paragraph) tag is our “selector” – it’s what we’re “selecting” to style. Selectors can either be standard HTML tags, or custom elements you define.

A “rule” is a set of properties that get applied to the selected element or elements. A rule can be as simple as a single line declaring the background color of the element, or a complex grouping of properties that work together to achieve an effect.

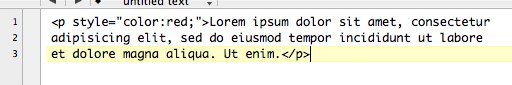

Let’s walk through styling a single paragraph. First, attach a style to an element on the page, and create rules as name:value pairs, separated by semi-colons. (You’re writing this all in your HTML page)

This single paragraph, the paragraph that you applied the color “red” to, will look different from every other paragraph on the page. The text will be red.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo …

Now, delete the “<p style=”color:red;> from your HTML page. Go into Text Wrangler and create a new page and call it style.css. This will be your EXTERNAL stylesheet. See the image below.

In the new style.css document you’ve created, write in the following:

p {

color:red; }Note: You must put this link inside the header tags. <link rel=”stylesheet” type=”text/css” href=”style.css” /> You can add as many rules as you want. See a few more below:

p {

color:black; font-size:12px; font-family:Verdana; }NO style tags are to be used inside your HTML document. Everything will be placed in an external stylesheet called style.css.

CSS Basics – HTML/CSS

CUSTOM SELECTORS

In the example above, every <p> tag will have ALL the attributes you list. This is a page-wide rule that is applied to all paragraphs on the page. That’s fine in some circumstances but what if you want to apply a specific attribute to a specific paragraph? CSS uses the “class” and “id” constructs to make this very eacy. By attaching a “class” name to an HTML element, and writing a corresponding rule for that class, you can get as specific as you like. Go back to the style rules above and modify them to look like this:

p {

color:red;

font-size:10px;

font-family:Arial;

}

.mango {

color:blue;

background-color:gold;

border:3px solid black;

padding 15px;

}

Now, modify the opening <p> tag of your paragraphs to look like this:

|

1

|

<p class="mango">Lorem ipsum ... </p> |

That specific single paragraph on your page will have the additional stylistic information taken from the style.css doc from .alert. That specific paragraph will now have the font color: red, font-size:10px, font-family:arial and everything listed under .alert. If you add <p class=”alert”> to another <p> tag on your page, that <p> tag will also have the same attributes. If you want another <p> on the page to have different and specifics attributes, simply name it something different. Example: <p class=”monkey”> and write the specific .monkey attributes in your style.css page.

CLASS VS. ID

There are two constructs for custom selectors — “class” and “id.” Class can be applied as many times as you like on a page. IDs work almost the same way, but apply to just one element on a page. When creating rules for IDs, simply prepend the selector name with “#” rather than “.” Example:

#footer {

color:#ff0000;

background-color:red;

border:2px solid black;

padding:20px;

}

Since you will probably only ever have one footer on a page, it makes sense to use this as an ID rather than as a class. You would invoke this ruleset in your document like this:

|

1

|

<p id="footer">Lorem ipsum dolor sit ... irure dolor in reprehenderit in </p> |

REFINING SELECTORS

Above we created rules that apply either to a single HTML tag, or to anything that matches a custom selector name. But we have a lot more control than that. You can broaden or narrow the “scope” of elements your rulesets apply to.

p, ol, ul, dd, blockquote {

color:#00ff00;

font-size:14px;

font-family:Verdana;

}

Now the rules in the set will apply equally to paragraphs, ordered, unordered and definition lists, and to blockquotes. If you want to set basic rules that will apply to your entire document, there’s an easier way — just use the <body> tag as your selector:

body {

color:#00ff00;

font-size:14px;

font-family:Verdana;

}

Since all visible elements in a document (elements that show up on your website) fall inside the opening and closing <body> tags, the rules above will apply to everything on the page. CSS favors the specific over the general so you can easily override any rule on a per-selector basis. For example:

body {

color:#000000;

font-size:14px;

font-family:Verdana;

}

blockquote {

color:#ffffff;}

Even though you’ve defined a color for the entire document within you <body> tage, and your block quotes fall inside that document, blockquotes will be rendered with a white font (#ffffff stands for white). The cascade says that even though everything on the page is black by default (you listed that in the <body> tag), blockquotes are treated like an exception.

Narrowing the Scope of Rulesets

We can also create the opposite situation. Above, I showed you the class .mango, which applied to anything on the page with class="mango". What if you want to be more specific than that or if you only want those rules to apply to paragraphs in that specific class, but not to blockquotes in that class. This is done like this:

p.mango {

color:darkred;

background-color:blue;

border:2px solid black;

padding:10px;

}

The rule above would not be invoked for standard paragraphs, nor would it be invoked for blockquotes with a class of “mango.” It would only be invoked for paragraphs with a class of “mango.” This “narrowing” approach can be used for IDs as well as classes:

p#mango {

color:darkred;

background-color:blue;

border:2px solid black;

padding:10px;

}

The rule above would not be invoked for standard paragraphs, nor would it be invoked for blockquotes with a class of “mango.” It would only be invoked for paragraphs with a class of “mango”. This “narrowing” approach can be used for IDs as well as classes:

p#mango{

color:darkred;

background-color:bisque;

border:2px solid gray;

padding:10px;

}

FONTS AND TEXT

You can set the font face (font-family), the font size, font style (such as italic) and the font weight (such as bold):

p {

font-family:”Arial”,Verdana;Georgia,Serif;

font-size:10pt;

font-weight:bold;

font-style:underline;

}

Font sizes can be set in pixels, points, ems, or relative values.

From within CSS you can control how wide your letters and lines are spaced, set your text color, align text right, left or center, and even change the case of text.

Setting text color and letter spacing:

Letter spacing can be set in points, pixels, or ems. “Em” is a typesetter’s term, referring to the width of one character. It is recommend to use ems when setting text sizes and widths, because it flexes automatically with the user’s current screen resolution and magnification.

Line spacing is not set in ems – it’s a simple decimal value representing a factor of the current line height. In the example below, “1.8″ means “spacing between lines should be 1.8 times whatever the current height of a line of text is.”

p {

color:#166A3F;

font-weight:bold;

letter-spacing: 0.3em;

line-height: 1.8;

}

If you wanted to make the text uppercase, just add the following line : text-transform: uppercase; If you wanted to change the text alignment, just add the following line: text-align: center|left|right; (You would need to choose either center, left or right). You could also add: text-align:justify; if you wanted the text to justify into a block.

BORDERS

You can put a border around almost anything on your page including a single character, an image or a section of a page. Borders can be of any thickness, any color, and can be solid, dotted, or dashed. If you use border: by itself, the border will go around all four sides of the element. Or you can use border-top:, border-left: and so on to control each side of the border independently. You can can consolidate all of the attributes of the border into a single command by separating the attributes with spaces.

Example:

p {

border:1px solid #4c97ff;

}

By not specifying a side, you get the same 1px consistent border on all four sides of an element. If you want to control each specific side of a border, use: (change the colors to what ever you like)

p {

border-top:3px solid #595128;

border-right:5px solid #3d3600;

border-left:2px dotted #5bbe00;

border-bottom:5px dashed #005062;

}

Using four different colors on a border would be pretty ugly so try his. A 1px border around a paragraph would look like this:

BACKGROUNDS

You can set the background of any element with your choice of either a solid color or a tiled (repeating) image.

Example:

p {

background-color:#00ff00;

}

If you want to use a tiled image as a background, just specify its relative or absolute URL:

p {

background-image: url(‘http://a3.twimg.com/profile_images/454374541/iTunesU_Button.jpg’)

}

By default, a background image will tile repeatedly in all directions, to fill up the space it’s assigned to. You can tell your background image to only repeat along the x or y axis. In the next example, we use both a background color and a background image. We tell the background image to only repeat vertically. To prevent the text from sitting on top of the tiled image, we add 120px of left padding.

p {

background-image: url(‘http://a3.twimg.com/profile_images/454374541/iTunesU_Button.jpg’);

background-repeat: repeat-y;

background-color:#D33333;

padding:10px;

padding-left:120px;

border:1px solid #899999;

}

MARGINS AND PADDING

Margins refer to the area around, or outside of an element. Padding, refers to the area between the edges of a box and what lives inside that box. An easy way to remember which is which is to think of mailing a breakable object – you fill the empty space in the box with foam peanuts to protect the item. Those foam peanuts are your padding. The margin would then be the space between your box and the next box in the truck. Just remember: Padding is inside the box, margins are outside the box.

In CSS, you’ll use padding to give an element some breathing room within the space it’s in, as we did with the last example in the Backgrounds section. You typically use margins to cause a box or element to be offset from adjacent elements. The syntax for working with padding and margins is very similar.

Padding and margins may just seem decorative right now, but they’ll become critical when we start getting into CSS page layout, so make sure you understand them.

Example:

p {

padding:25px;

border:4px solid blue;

}

Would give you below:

Just like borders, padding can be controlled for the whole box, as above, or per-side:

p {

padding-top:0px;

padding-right:25px;

padding-bottom:45px;

padding-left:15px;

border:4px solid blue;

}

When setting padding values separately for different sides of a box, you can use this shorthand, which achieves exactly the same result as the previous example:

p {

padding:0px 25px 45px 15px;

border:4px solid blue;

}

MARGINS

To illustrate how margins work, I’ll show you how one element (box) relates to another. For this example, we’ll be putting a sample paragraph inside of an element called a “div”. A div is an arbitrary box used to contain other things. I’ll put a border on the div so you can see it, then put a paragraph with its own border inside that div, so you can see what the margin attributes do to it.

div {

padding:0px;

margin:0px;

border:1px solid blue;

background-color:#AFEEBD;

}

p {

padding:10px;

margin:10px;

border:1px solid blue;

background-color:#ACCFDB;

}

The blue space above represents the paragraph, while the green space represents the margin between that paragraph and it’s containing box. As with padding, we can control margin depths per-side, rather than globally.

LISTS AND CSS

An ordered or unordered list can be much more than a simple set of bullet points – in CSS, lists are often used to create navigation elements such as horizontal or vertical menus. Let’s start with options for simple lists.

For unordered lists, you can select whether the bullet style should be circular, square, or none:

ul {

list-style-type: square;

}

apple

Is a

List

Try changing “square” to “circle” or “disc” for other effects. You can also use an image in place of your bullets by specifying its URL:

ul {

list-style-image: url(http://www.w3schools.com/css/arrow.gif);

}

This

Is a

List

Ordered lists can have any combination of Roman numerals, decimal, alphabetic characters and more. A nice trick is to nest lists within lists, then use the CSS nested selector syntax we learned earlier to style different levels of your list differently, like this:

ol {

list-style-type: upper-roman;

}

ol ol {

list-style-type: decimal;

}

ol ol ol {

list-style-type: lower-alpha;

}

Person

Place

Region

Country

United States

Canada

Mexico

State

Thing

In the example here, ordered lists “ol” are told to use “upper-roman” as the list-style-type, unless it’s an ordered list inside of an ordered list, in which case the list-style-type is “decimal”… unless it’s a triply nested ordered list, in which case the list-style-type is “lower-alpha.” This technique is the key to building CSS based flyout navigation menus.

LISTS AS MENUS IN CSS

By default, list items are “block-level elements,” which means each one gets a line break above and below itself. To make a list appear horizontally, we need to override the default block behavior and use CSS to tell list items that they’re “inline” elements instead. In this example, we’ve also added background-color and padding to our list items, to make them appear like real menu items. Here is the simple HTML and CSS to create a basic list menu.

li {

display: inline;

list-style-type: none;

background-color:#425899;

color:white;

padding:5px;

}

<ul>

<li>Item one</li>

<li>Item two</li>

<li>Item three</li>

<li>Item four</li>

<li>Item five</li>

</ul>

Which seen by the browser it looks like this:

To make the experience more intuitive, we want to add some rollover behavior, so that the list items change color when the mouse rolls over them. To accomplish this, we’ll first make our list items into links (in the HTML). Then we’ll again use the CSS nested selector syntax to detect a linked item inside of a list item. Finally, we’ll use the anchor tag’s :hover pseudo-property to change appearance when a list item is in a certain state – namely, when the mouse is hovering over it.

li {

display: inline;

list-style-type: none;

}

li a {

background-color: #60996C;

color:white;

padding:5px;

text-decoration:none;

}

li a:hover {

/* This rule is only in effect when mouse is hovering */

background-color: #567499;

}

<ul>

<li><a href=”#”>Item one</a></li>

<li><a href=”#”>Item two</a></li>

<li><a href=”#”>Item three</a></li>

<li><a href=”#”>Item four</a></li>

<li><a href=”#”>Item five</a></li>

</ul>

See below. Roll mouse over list items to see the hover state in effect.

HOMEWORK | WEEK 4

If you receive any comments from me today in class, or via email in the following week, incorporate them into your pages.

Watch the “Box model with css” video on this page again. Create a new page and call it boxmodel.html. Make sure you update you navigation list in your other pages to add this new page. In your boxmodel.html page, create a page with the black, green red and blue boxes that looks exactly like what is in the video. Make a SPECIFIC css document for this boxmodel and call it boxmodel.css.

Post the new work and link it to your homework page.

Create your nav document in Photoshop and using the code I’ve supplied above, create a new nav for your HTML pages.

Somethingtoosee.net

http://julliehusclarkeclayton.wordpress.com/

Although I will not be in class today, If it ever happens again I will email you. The links above is what ive completed so far. My apologies for the in professionalism.

present

present

http://tbennettweb1.wordpress.com/

http://www.travisbennettportfolio.com/

katthompson.net

– I’m having with cyberduck so nothing is current.

present

http://www.chadburnham.com/